Interview with Beth Dooley

This interview is part of a series which highlights the work of various individuals and organizations within the Kernza® network. Through these interviews, we aim to share and celebrate that there is a large and ever-changing ecosystem that moves Kernza® perennial grain forward. If you would like your organization’s work to be featured in an interview, please email Sophia Skelly. To learn more about the Kernza® network, visit our directory.

Beth Dooley is a James Beard Award-winning food writer who has authored and co-authored over a dozen books celebrating the bounty of America’s Northern Heartland. She writes for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, appears regularly on local TV and radio, and publishes the Bare Bones Cooking newsletter with her middle son Kip.

Can you tell me about your engagement with sustainable and regional agriculture?

We moved to Minneapolis about 45 years ago but I’m from New Jersey originally. I’ve always been a writer and I’ve always been interested in food. So one of the first things I did when we got to Minneapolis was join a CSA and learn about our local food system. I always want to know how the food is grown and how it gets to us because it informs the flavor and quality. As I wrote about food in the local paper and other publications, I began to recognize how important this area is. We are America’s breadbasket. I became really interested in the history of wheat and how it built our area’s economy, the traditions behind it, and how it has changed over time. I learned about Norman Borlaug and the hybridization of contemporary wheat. Shortly after, I met Don Wyse and he introduced me to the work of Wes Jackson and The Land Institute.

I’m excited about the work on perennial grains because to me, this work is really hopeful. There is so much bad news about food. I’m enough of an optimist that I can let other folks write about the ravages of industrial agriculture.I know it’s horrible and that it will collapse on its own. I’d rather write about the solutions and try to engage home cooks with understanding the work being done that’s providing those solutions. I think Kernza® grain is one of those foods that provides a lot of hope.

I’d rather write about the solutions and try to engage home cooks with understanding the work being done that’s providing those solutions. I think Kernza® grain is one of those foods that provides a lot of hope.

You engage with researchers, farmers, millers, home cooks, and others. Can you talk about your experience being at the nexus of so many different types of knowledge? What are the challenges and the opportunities in playing that role?

There are plenty of challenges because I’m not a scientist and I’m not a professional chef. I’m simply a food writer and a home cook. I follow all these people around with my pen and try to decipher what they’re talking about and how to translate it into other people’s homes. I find it terribly exciting and humbling at the same time. I don’t have to know everything; I just need to present enough of the information that if somebody is truly interested, they can then go and research that particular topic on their own. I’m a jack of all trades and a master of none.

I think that relates to how the Kernza® network operates more broadly. There’s a lot of collaboration and re-directing folks to people with very specific knowledge. People often say, “I actually don’t know how that works, but I know this person that does…”

Totally! That type of environment is sort of embedded in what cooks have always done, right? Cooks have always said “my pound cake recipe is okay, but I actually got it from Loretta, who makes a much better pound cake. You should talk to her about what she does.”

I think the kitchen is a place where there are a lot of those conversations and information is shared on a more informal level. To me, that’s the thing that cooking does. It connects cooks to this work at a more personal level.

Can you talk about how that intersects with accessibility and equity? Many of these crops are still in a nascent stage in the supply chain; how are you thinking about how to communicate the benefits of these products in an accessible way?

That’s a really good question and it’s always difficult to answer. Right now, Kernza® is $10 for a bag, so you have to really want it in order to buy it. I also think it’s important that we recognize the rural disparity and rural poverty, which often gets left out of the conversation when we’re talking about equity. If we can regenerate a lot of those farms, and create opportunities for more people on the land, grow more things in rotation, and maybe even get more labor on the land, that’s going to revive a lot of our rural communities that have been totally cut out of economic systems. Maybe, if we can do that, there will be schools again. There will be libraries in those towns. We’ll have more broadband and internet.

Also, perhaps there’s a political component to this as well. We can press politicians to shift a lot of the commodity price supports and crop loss insurance monies that support growing bad food, and move them towards growing good food. The price of that food will come down and that will make it more accessible to more communities.

I also know that there’s a lot of work being done in our area. For example, The Good Acre is a nonprofit food hub to support Black, Indigenous, and People of Color farmers and support their markets. There’s no reason why those farmers can’t have access to Kernza® and to be able to grow a crop that has these ecological services and provides a really good price. There’s a whole lot of things that have to change.

Looking into the future, Do you have any specific plans or aspirations related to Kernza® or other perennial grains?

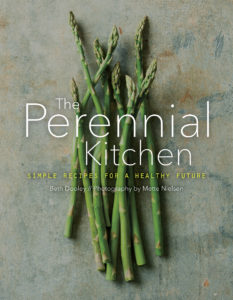

The Perennial Kitchen came out this May. The University of Minnesota Press published it and there has been a lot of interest in it.

It’s also exciting that a lot of people are familiar with the term regenerative agriculture. It’s not a perfect term because it speaks to agriculture, and right now, “agriculture” has an association with crops like corn and soy, not with things that you’re going to cook in a pot at home. I’m hoping that this book will be a bridge because it has information in it about all kinds of foods that can be grown either at scale or on small farms. It has a lot of information about grass-fed meat and about the different animals that we need to return to the land for a variety of reasons. It argues against the idea that we need to go into a strict, plant-based diet. It tries to answer why fake meat isn’t the answer. In my mind, fake meat is just one more industrial answer to a problem that has been created by our industrial food system. I tried to press back against the argument that plant-based diets are the way to abate climate change. But it’s always a tricky balance. I’m a food writer. When I get on too much of a soap stand, people tune me out. But I’ve always found that recipes are a nice delivery system for information that people might not come across on their own.

You mentioned that “regenerative” is becoming a common term. I’m curious what you’ve witnessed in terms of the word “perennial.” How does it register with people? What is their understanding of it?

I think they like it better. It’s easier for them to get their heads around. They think of the plants in their garden. They likely have more experience with perennial plants than they do with “regenerative crops.”

I think we also have to be aware of locking these terms in, or making them too codified, too marketable. They lose their bandwidth and they also are in danger of becoming commodified again. I think one of the most interesting things I’ve heard in the discussion around Kernza® is from growers who are now forming grower co-ops. They are saying that if we allow this grain to become another commodity, we’re not doing it right. I think it’s really important to keep reminding people that this is not a commodity crop. It’s hard for people to wrap their heads around what that means.

Do you have a favorite Kernza® food or drink?

Sandy at Bang Brewing makes a wonderful beer called Gold, named after the University of Minnesota because their colors are maroon and gold. In terms of my own Kernza® recipes, I love the shortbread. It’s really delicious because I find that Kernza® grain often tastes a little different, depending on where it’s grown. I think it’s beautiful that it will retain some of its flavor notes – in some areas, it’s going to be grassier and in other areas it’s going to be more nutty.

The shortbread is nothing more than butter, brown sugar or maple sugar, and Kernza® flour. And the Kernza® flour from Perennial Pantry has a wonderful graham-like taste to it, so it’s delicious in shortbread.

Photographs by Mette Nielsen.